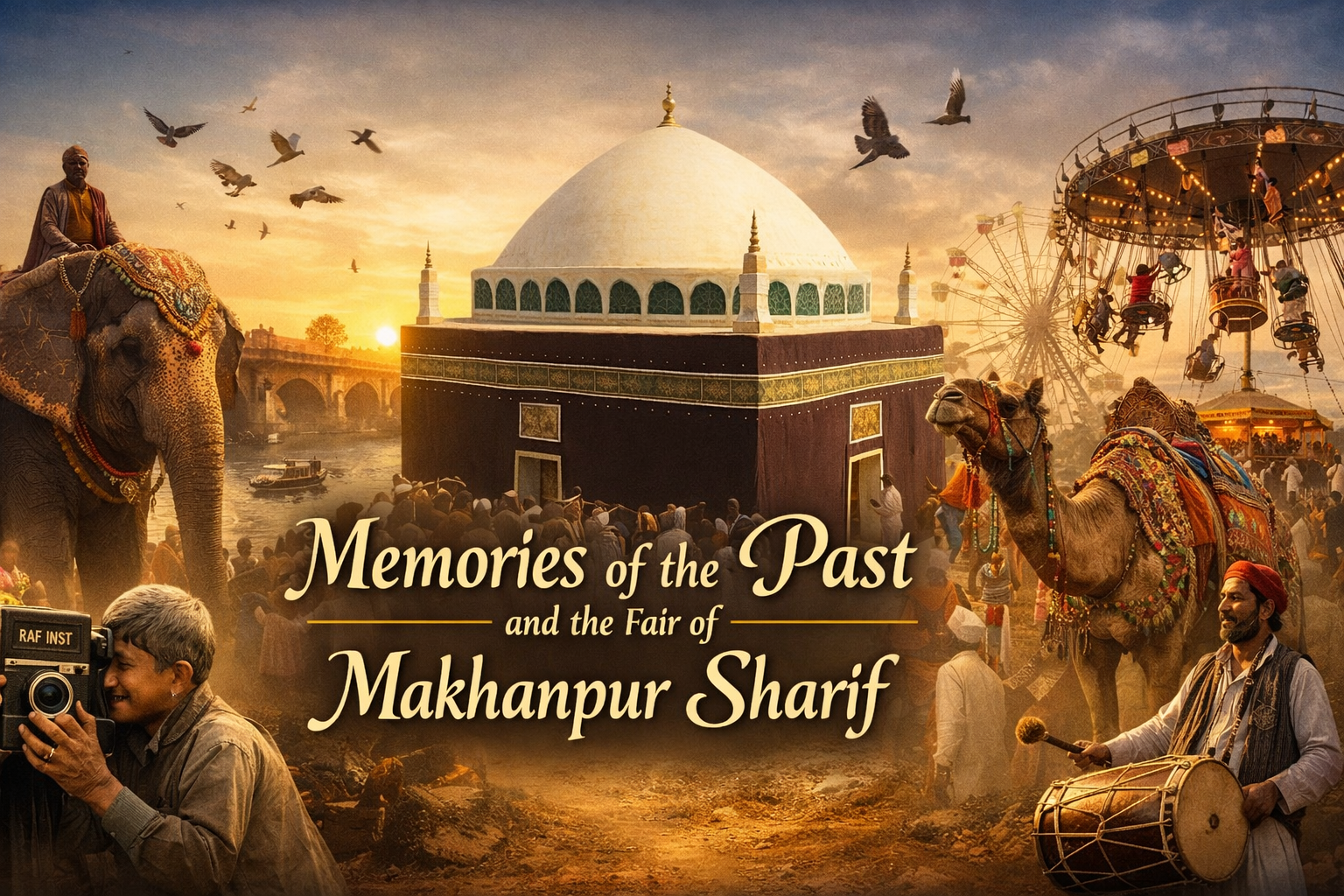

Ancient Makanpur

a beautiful masterpiece of the Creator of the universe, settled low beside the banks of the River Isan, perched amid sandy dunes, adorned with groves of date palms. Along the edges, transparent, silvery sands shimmered; large courtyards fragrant with flowers and garden beds; yards and platforms plastered with yellow earth; walls coated with whitewash and decorated with floral motifs, with occasional palm branches—like Diwali gateways beautifully adorned. This lovely scene seemed no less than a palace of pure marble. In places, creepers of bottle gourd climbed over thatched roofs.

Flowerbeds were decorated with fine plants and blossoms—roses, guldopariya, marigold, gulfarang, chrysanthemums, and many more.

Every home presented a charming sight. I remember that era when Makanpur Sharif had unpaved paths, and for small errands bullock carts were used.

The people of the settlement would joyfully and eagerly board the bus parked across the river to go to the city of Kanpur. Early in the pleasant mornings, when the bus across the river sounded its distinctive horn, the households of the village knew that the bus had arrived. Before time passed, anyone heading to the city—or anyone seeing off a guest from home—had to cross the Isan by boat, as there was no bridge over the river.

Since no permanent bridge had been built on the Isan, every year before the Magh Fair at the Dargah of Zinda Shah Madar, held on the occasion of Basant Panchami, a temporary earthen bridge was constructed over the river in the rosy chill of winter. When the bridge was completed, a date was fixed for its inauguration. A truck would be brought, a little cargo placed on it, and young boys and children would sit on it. The truck would then be driven across the temporary bridge. Once it successfully crossed from one bank to the other, it would proceed straight to the holy shrine, where sweets like batasha were offered in prayer and distributed. That day was considered a day of great joy—no less than Eid.

It was called the day the “thela passed.” People would congratulate one another with overflowing happiness, saying, “The thela has passed.” Gradually, trucks began to cross regularly and the fair would commence.

Preparations for the fair began using this very bridge. Narrow paths laid with brick fragments, bordered and beautified by thorny cactus trees; here and there datura trees in bloom looked beautiful; patches of greenery and dryness, with grasses like kans and kasaundi, added to the charm of the route.

Around the town, fields spread over acres were adorned with bright yellow mustard flowers. On the slender, bending leaves of sugarcane, birds chirped, swayed, and played. Sometimes a horse-drawn cart raced along the road; sometimes beautifully decorated camels or bullock carts carried goods to the fair.

In the fairgrounds there were hundreds of wells. Before the fair, the wells were cleaned; rain-eroded land was filled; pits were leveled; soil was added where needed; cleanliness drives began. Grass cutters arrived a month in advance, cutting grass and piling it up; heaps of fodder were prepared; water carriers came so that water could reach every required spot.

It was a very large fair—unique in the entire country. Apart from livestock, there was hardly any trade item or household good that could not be found there. From a needle to an elephant—everything was available.

The special feature was that each category had its own separate market: elephants had their own market, camels another, buffaloes another, oxen another, horses another, goats another, donkeys another. Even within these, there were separate sections for young animals, adults, and old ones; for superior breeds, black ones, white ones, medium-quality animals, sturdy ones, and weak ones.

Likewise, every commodity had its own lane and market: timber yards, anklet lanes, ironware, boxes, quilts, cloth markets, bangle lanes, general merchandise, halwa and sweets, food stalls, crockery, comb markets, utensil bazaars, main avenues, confectionery markets, shoe and sandal markets, kohl lanes, dental tools, grinding stones, bedding, toy markets, and many more.

For children’s entertainment there were games, shows, swings, circuses, the “well of death,” and similar attractions, all set up in separate grounds.

Visitors and traders stayed in huts and temporary shelters. Throughout the fair there was enjoyment of every kind: somewhere stoves were sold; somewhere paan and bidis hung from a vendor’s neck; somewhere hot tea; somewhere fodder for animals; the rhythmic sounds of farriers shoeing animals delighted the ears. As soon as the bells rang at the makeshift cinema run by an old woman with a box slung around her neck, children would run toward it.

The surroundings of the Dargah Sharif of Zinda Shah Madar remained fragrant with the sweet aroma of incense, and the air echoed with cries of “Dam Madar.” Devotees circumambulated the shrine with ceremonial cloths on their heads; some offered roosters, some fulfilled vows, and in places head-shaving ceremonies took place.

The greatest thing was that disputes which could not be resolved by village councils were settled in the fields of Madaran. People who had fought all year, who had cut off relations, nursed enmities and tensions, would come there, swear an oath, and everything would end. This was one of the fair’s most important virtues.

Basant Panchami brought days of blessing in a delightful season and a joyous atmosphere.

The fair was so vast that it was difficult to cover; one would tire while roaming, yet even in four or five days it could not be fully seen. In the camel market, camel handlers would beat plates all night long, singing invocations to Madar. The gurgling and muttering sounds of camels were heard across the settlement. Early mornings, flute sellers would wake children with their tunes, and children—rubbing their eyes—would hurry to them.

Across the fairgrounds, performers would beat their drums to gather children and call the elders, then present their shows. In short, it was a delightful scene in a pleasant climate.

Everyone remembers the loudspeaker of the neem-cool kohl seller. The district administration ensured adequate police arrangements; police from 52 districts came to the fair. Checkposts and temporary police stations were set up; mounted officers patrolled the grounds. The fair committee of Tehsil Makanpur arranged for sprinkling water on the unpaved roads.

Among the fair committee’s special events were an All-India mushaira (poetry symposium), kavi sammelan, public gatherings, orchestra performances, communal feasts (langar), ceremonial cauldrons, and the presentation of the sacred chadar—held under the chairmanship of the current SDM. The fair was inaugurated by offering a chadar at the shrine of Sarkar Qutub-ul-Madar. On that day, the Syeds of Makanpur Sharif, Sufi elders, scholars, members of the fair committee, and respected Hindu and Muslim brothers all participated.

This inaugural chadar procession came from the fairgrounds to the Khanqah Sharif under the chairmanship of the District Magistrate. At the Dargah Sharif, the chadar was presented at the court of Madar-ul-Alameen, and turbans were tied on the heads of the officers from the Khanqah. Then the fair formally began. The most special day of the fair is Basant Panchami, when the Qul ceremony is held at the shrine. Its unique feature was that throughout the entire fair, a single clap would resound at once—God knows where it began and where it ended—and with that clap, the Qul was announced.

The fair still takes place today, as it did yesterday. It is known for Hindu–Muslim unity. The public has not decreased; rather, the crowds have grown. However, in this era of development, new inventions have impacted fairs: livestock trade has ended, replaced by vehicles; thus the livestock fair has nearly vanished. Other necessities are now available everywhere; markets have sprung up in every lane; online sellers deliver goods to doorsteps. As a result, the commercial structure of fairs has been affected—and not just fairs, but the whole world has changed: times have changed, paths have changed, people have changed, seasons have changed, affections have changed. Tongas and bullock carts have nearly disappeared; even modes of transport have changed; bicycles have been put away; traditional fair entertainments have changed; trees have been cut; sparrows have flown away; crows no longer sit on rooftops; the chirping has fallen silent; grass has grown over footpaths; and people in every settlement, town, and village have grown estranged from one another. Generations have changed; care, concern, and empathy have faded; and thus a beautiful, love-filled era came to an end.

Mutual love and affection—and above all, sensitivity—have vanished. One’s own became strangers; strangers became one’s own.

In earlier times, when it rained, people prayed for one another’s well-being. After a night of heavy rain, elders would go from house to house at dawn—checking if anyone’s thatched roof had fallen, if a room had collapsed, if a wall had come down; asking about injuries or losses; helping lift belongings trapped under fallen roofs and taking responsibility to move them to safe places.

Children joyfully ran, played, and bathed in muddy rainwater. Wild fruits, berries, mango pits, and jamun sustained us through the monsoon. Those carefree days of joyful poverty were so beautiful—there was no narcissism, no deception of the world, no envy, arrogance, lies, or tyranny.

But now all this remains only to be spoken of and heard.

Where have those days gone?

— Written by Syed Azbar Ali Jafri Madari, Makanpur Sharif